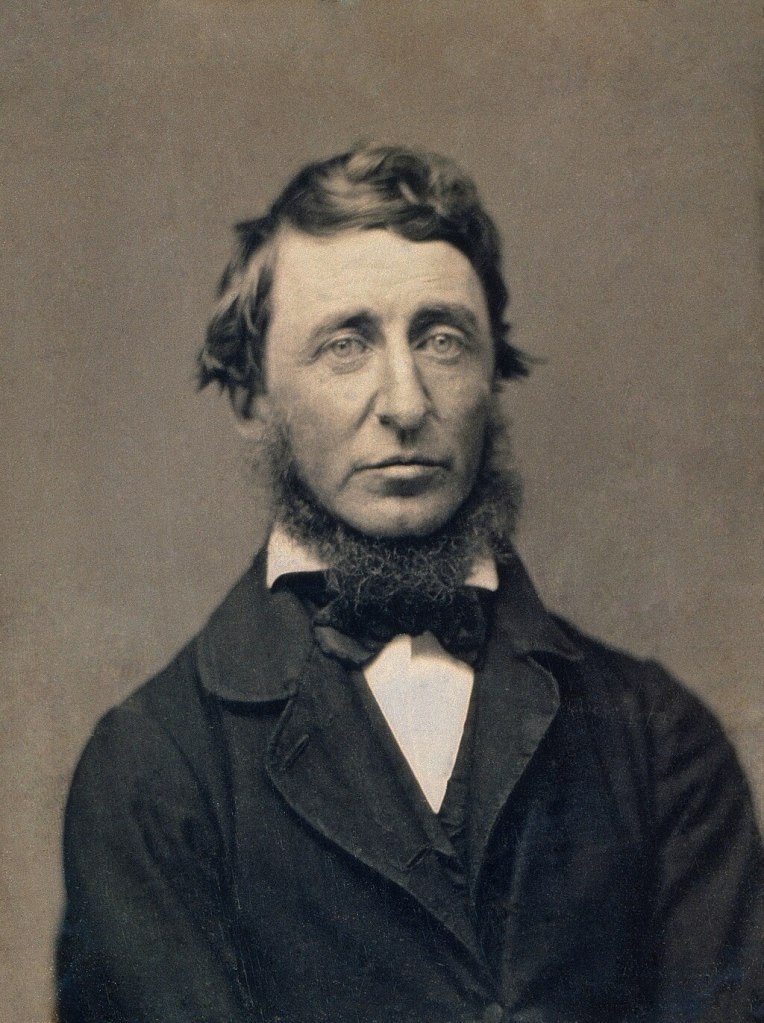

While the title of this essay may come across as rather dystopic, I feel I can express it with no less urgency nor importance that now, as we are heading into the second quarter of the 21st century, Thoreau’s Walden seems more important than ever.

If you are yet to read Walden; this fantastic, beautiful, eloquent, thoughtful, at times persuasive, at times hilarious work, it may be that you should — as this essay will champion; and, while thus I yearn to make a strong, compelling case for why Thoreau is to be studied, and read, and subsequently reread; as the ideas he exercises are, arguably, just as valid today as they were some 170 years ago when he wrote Walden, alone in the woods, in a state of what one, rightfully, and in the spirit of Montaigne, can call an “awakening,” I do not, as it happens, labour under the illusion that the modern reader will find Walden nearly as enjoyable as he/she should.

However, luckily I am to an extent so far as my passion for literature is concerned, an optimist, and I hope, with the help of my long-dead mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson, that the desire and hunger for reading Walden will be awoken for the patient reader of this essay.

And apropos Emerson, let me begin with the mentor and good friend of Thoreau, who described quite succinctly the Thoreauean mission in his own essay Thoreau (1862), which will set up the premise for the ensuing text:

“He [Thoreau] declined to give up his large ambition of knowledge and action for any narrow craft or profession, aiming at a much more comprehensive calling, the art of living well. If he slighted and defied the opinion of others, it was only that he was more intent to reconvene his practice with his own belief.” (Emerson: Thoreau 1862).

Before embarking on finding out exactly what “the art of living“ is for Henry David Thoreau, it is necessary first to look at Thoreau the man, opposite to Thoreau the character, whom we see fleshed out in Walden. Like Walter Whitman Jr., the Brooklyn journalist, who wrote ‘Leaves Of Grass‘, he too creates his alterego in Walt Whitman, the seeker and the poet in his Song Of Myself. This will be important as Walden and Song Of myself share many similarities, and, interestingly, they were published somewhat at the same time without having directly influenced each other, as if (yes, I dare go there —) they were unified by a single origin!

It is of much importance — especially in the case of certain poets; of which Thoreau is a part — to distinguish between the poet and the alterego, as the two, often, will be in conflict with each other. And as such, there can arise what is on the surface-level inconsistencies between the two, which, however, when the text is properly dissected and read, proves to be less about inconsistencies, and more about the reader failing to understand the subject matter at hand.

As for Thoreau the man, he was someone who took pride in less, rather than more, to quote his own journals:

“They make their pride in making their dinner cost much; I make my pride in making my dinner cost little.” (Emerson: Thoreau 1862).

By having fewer possessions, and by having fewer needs, Thoreau in a sense made himself rich, prosperous, and kept his soul healthy and free from the consumerism he so detested. He further notes in his journal:

“I am often reminded that if I had bestowed on me the wealth of Cræsus, my aims must be still the same, and my means essentially the same.” (Emerson: Thoreau 1862).

Wealth, as is evident in this rather pompous proclamation, will change nothing for Thoreau; he is not transfigured by it, nor is it a convincing tool with which his attention will steer from his true “aim“; which is, in the end, the art of living well.

Finally, Thoreau had little if any vices. He was known to neither drink, gamble nor smoke, to quote again from Emerson’s essay on Thoreau: “I have a faint recollection of pleasure derived from smoking dried lilystems, before I was a man. I had commonly a supply of these. I have never smoked anything more noxious.” (Emerson: Thoreau 1862). I have highlighted this early as this will be crucial to keep in mind in order to understand the psychology of the man Thoreau.

As for biographical data on Henry David Thoreau, I feel, as I have expressed in essays previously, that presenting any biographical or factual knowledge on an author, seems, unfortunately, a rather superfluous task in this day and age of hyperinformation (something Thoreau himself rebelled against; yes, 170 years prior), where any reader can quickly find out the who, when, and where of any given prolific person. So, instead of such futile task, I would rather take to looking at Thoreau, the character, as he is represented in Thoreau’s Walden, through the lens of essayistic analysis and dissection, and set up a case for why any 21st century reader should read Thoreau before, as the title implies, it truly is too late.

In this essay, more concretely, I will delve into specific passages and exercise them in order to unravel and make easier Thoreau’s thoughts and ideas; an effort which will, I hope, lead the reader to further investigate, and treat Walden as a manifesto of the greatest importance, especially considering the times toward which we are headed.

Now, without further ado: Walden, Thoreau, 1854.

Ticknor and Fields. Penguin Classics version: 2017.

Walden, in its essence, is about Thoreau’s experience living alone in the woods for around two years (two years, two months and two days to be precise), building his own house near Walden Pond, on land owned by before-mentioned Ralph Waldo Emerson. Walden details many aspects of his living in the woods, from the basic economy of the house, which cost him, curiously: $28,12½, to his living expenses and the cultivation of beans and other edible plant-material, continuing further to a variety of philosophical, poetic, historical, speculative, and political discourses on subjects ranging from materialism to solitude, reading, sounds, people, Nature, and to social interactions; and he does so in a format rather like that of Emerson or Montaigne, though in a more poetic and one could say (for better or worse): rebellious format.

Emerson wrote of Thoreau, rather humorously that he, “did not feel himself except in opposition,” and, “it seemed as if his first instinct on hearing a proposition was to controvert it, so impatient was he of the limitations of our daily thought.” (Emerson: Thoreau, 1862). I call this to attention as it becomes evident, rather quickly, that Thoreau is a man of a strong oppositional view; and of convictions, will-power, intellect, wit, humour, and self-reflection far surpassing that of most. This proves vital when considering Thoreau’s statements on the first page of Walden,

“In most books, the I, or first person, is omitted; in this it will be retained; that, in respect to egotism, is the main difference. We commonly do not remember that it is, after all, always the first person that is speaking. I should not talk so much about myself if there were any body else whom I knew as well.” (Walden: page 1)

This statement is an obvious parallel to that of Shakespeare, meaning the deep, introspective knowledge one is to achieve when reading the Shakespearean canon. Prof. Harold Bloom, in his Shakespeare: the invention of the human (1998), and other essays on Shakespeare, sets up the two “trees” if you will, the Cervantean Tree (think Don Quixote by Miguel De Cervantes), where the characters come about their self-actualisation through talking to one another (dialogue), contrary to that of the Shakespearean Tree in which the characters (and the reader!) is taught how to overhear one’s self, to talk to one’s self, in essence: by understanding and reading Shakespeare we become self-reflective beings, in the pursuit of knowing our self’s, as a means to further achieve self-actualisation.

Goethe equally highlights this in his wonderful essay Shakespeare Once Again (1815) where he discusses how Shakespeare achieved what in literature is the highest of goals, which is to truly know one’s self. Or, as Hegel remarks in his lecture on Aesthetics, of which Shakespeare plays an important role, that,

“The more Shakespeare on the infinite embrace of his world-stage proceeds to develop the extreme limits of evil and folly, to that extent. . . he concentrates these characters in their limitations. While doing so, however, he confers on them intelligence and imagination; and by means of the image in which they, by virtue of that intelligence, contemplate themselves objectively, as a work of art, he makes them free artists of themselves, and is fully able, through the complete virility and truth of his characterization, to awaken our interest in criminals, no less than in the most vulgar and weak-witted lubbers and fools.” (Hegel: Lectures on Aesthetics, c. 1821).

Now, Thoreau was obviously a very well-read man, we will later see this in his chapter on Reading, and he treated Shakespeare (and rightfully so) as an essential entity in our canon. Hence, when Thoreau rather provocatively writes:

“I should not talk so much about myself if there were any body else whom I knew as well.”

It is because he, considering himself both a true poet and a true philosopher, has come about the self-actualisation and the self-reflection, like a Hamlet or a King Lear, which he now seeks to convey to us, the reader — not that Thoreau, to be fair, expects us to come about this easily.

It starts, in many ways, with freedom, the pursuit of it, and the cultivation of it, when it is achieved. Living alone in the woods, and leading a life largely removed from society, and appreciating above all his freedom, Thoreau saw in his townsfolk how big of a,

“(…) misfortune it is to have inherited farms, houses, barns, cattle, and farming tools; for these are more easily acquired than got rid of. Better if they had been born in the open pasture and suckled by a wolf, that they might have seen with clearer eyes what field they were called to labor in.“

Inheriting such property that requires the endless cycle of work and labour is for Thoreau antithetical to that of coming closer to the ‘art of living well’, which is his ultimate goal; because who, he asks, pointedly, has time to truly live freely and finding one’s self when one is chained from the very beginning of life; or, as he writes:

“Why should they begin digging their graves as soon as they are born?“

And he follows this up with,

“But men labor under a mistake. The better part of the man is soon ploughed into the soil for compost. By a seeming fate, commonly called necessity.”

Now, Thoreau was a rather young man when writing Walden, and for most people, with any sense of economic, political and realistic sense, one knows work is for the majority a necessity. I have no doubt that Thoreau (the man! not the character) would not dispute this; but the way one comes about the work is a crucial factor for Thoreau. And, as it happens, what comes before and after one settles for work is equally crucial. Will one settle and forget one’s responsibility to cultivate the “spiritual and intellectual faculties“; will one abolish the importance of living with deliberation. Thoreau writes in the chapter of reading:

“With a little more deliberation in the choice of their pursuits, all men would perhaps become essentially students and observers (…)”

I must stress that it is for Thoreau not about becoming a hermit, or a hobo, or living without people. It is, as Walden will show us, about living with deliberation, and this will require periods of deep solitude (as it does for Whitman’s process as well), and it requires studying, effort, Nature (with a capitalised N), and social interaction, although social interaction especially should be used but sparingly.

Thoreau himself chose his social environment with both deliberation and serious consideration, thus he had,

“(…) three chairs in my house; one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.”

In Thoreau’s worldview, too many of us are too social. We see each other too often without having anything new to contribute with. This is an important aspect for Thoreau; who, 170 years ago, already then criticised the post-office for delivering too much information, the newspapers for giving us an all but repetitive structure of events (without anything new to contribute), and too many casual gatherings with the people around us, before we, ourselves, have changed enough to contribute with something different to the conversation. Different, that is, outside the borders of day-to-day living.

We end up with repetitions upon repetitions, which does not provide us with much, but a certain decadence, and a misalignment with ‘the art of living well.’ Thoreau reveals part of this idea through a simple yet beautiful story, concerning a visitor at his cabin, who had inscribed the following on a yellow walnut leaf, as Thoreau himself was not present:

“Arrived there, the little house they fill,

Ne looks for entertainment where non was;

Rest is their feast, and all things at their will:

The nobles mind the best contentment has.“

Read these sentences again and again, and assimilate the weight of these words, which were quoted from Edmund Spenser. Think, for a moment: who, in this day and age, can with all honesty claim that Rest is their feast, and who has the “contentment” only the nobles mind has, meaning who can find entertainment where none entertainment is? It is rather bleak and grave how most seek and find their pleasure(s) now, and though many will scuff at the word “soul” I find this Emersonian passage from his essay Spiritual Laws of great relevance:

“I desire not to disgrace the soul. The fact that I am here certainly shows me that the soul had need of an organ here. Shall I not assume the post? Shall I skulk and dodge and duck with my unreasonable apologies and vain modestly and imagine my being here impertinent?” (Emerson: Spiritual Laws, 1841).

One must ultimately choose where one directs the limited attention and time we have; too much entertainment drowns out the time when we are most in need of no entertainment at all; when our “self” needs cultivation. Emerson desires not to disgrace his soul, and nor should you. I find that Isabel Archer in Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady says it quite well,

“One ought to choose something very deliberately, and be faithful to that.” (James: The Portrait of a Lady, 2009).

Anything outside what has been chosen deliberately should be used sparingly, cautiously, rarely.

Now, as for the nuances and considerations of social interaction, Thoreau writes,

“Society is commonly too cheap. We meet at very short intervals, not having had time to acquire any new value for each other. We meet at meals three times a day, and give each other a new taste of that old musty cheese that we are. We have had to agree on a certain set of rules, called etiquette and politeness, to make this frequent meeting tolerable and that we need not come to open war. We meet at the post-office, and at the sociable, and about the fireside every night; we live thick and are in each other’s way, and stumble over one another, and I think that we thus lose some respect for one another. Certainly less frequency would suffice for all important and heart communications.”

Imagine Thoreau writing this some 170 years ago; if, thank God he isn’t, were to see the way in which we have designed our society today, with our almost incessant need for constant communication(s), he would no doubt have thought we were approaching the end, or at least, an end, however abstract or concrete. Even the “set of rules, called etiquette and politeness” which applies when one is tête-à-tête with a peer, no longer applies as we have now alienated ourselves entirely through our devices and technological ‘advancements’ such advancements as they are. In other words: one can say anything anytime to anyone without repercussions.

I think it is important again to stress the point: less social frequency provides more value when meeting one’s peers. Meeting too regularly and too often is a mindless practice with which we show, instead of new sides of ourselves, we rather “give each other a taste of that old musty cheese that we are.”

Is there a solution then? How do we develop enough in order to contribute to our own self-actualisation, and to our peer’s?

To this there are several aspects in Walden, although for the sake of this essay’s length, I have chosen to elucidate two especially,

1. Reading

2. Solitude

Thoreau understood the cognitive power of literature, and he understood, more importantly, the gravity of reading good literature, meaning the Bloomian concept that one must wrestle with our canon; one must read the classics.

Thoreau writes,

“Men sometimes speak as if the study of the classics would at length make way for more modern and practical studies; but the adventurous student will always study classics, in whatever language they may be written and however ancient they may be. For what are the classics but the noblest recorded thoughts of man?”

I need not unravel a long and tiresome discourse on how the classics, contrary to popular belief, is a way to pave for actual (and equally “modern” whatever word that means —) cognitive, spiritual and intellectual abilities; I have already done so in my essay Defending The Western Canon. I would rather like to stress the importance of how reading the classics is an exercise with which we truly develop our “intellectual faculties“, as Thoreau calls them. Unfortunately, the modern day reader has all but lost the ability to read what is essential, beautiful, strange, important, and of the highest aesthetic order. In fact: instead of reading books that can “compensate a lifetime’s rereadings” (Bloom: The Western Canon, 1994), most fall prey to low-quality entertainment with as much value as reading the supermarket receipt.

In Thoreau’s time, at least the entertainment-seeker, more often than not, had to read, and the information available was not unlimited, whereas today, with the continual growth and evolution of the great grey sea that is the internet; of technological devices and of social media platforms, it is an all but impossible task to ask of people to read — well, anything. . . And worse, 21st century entertainment bases itself on material so brutally hollow, and so all-consuming, that David Foster Wallace’s ‘Samizdat‘ or ‘Infinite Jest‘ seems an almost mild sort of prospect.

Thoreau fleshes this out gravely,

“All this they read with saucer eyes, and erected and primitive curiosity, and with unwearied gizzard, whose corrugations even yet need no sharpening, just as some little four-year-old bencher his two-cent gilt-covered edition of Cinderella, — without any improvement, that I can see, in the pronunciation, or accent, or emphasis, or any more skill in extracting or inserting the moral. The result is dulness of sight, a stagnation of the vital circulations, and a general deliquium and sloughing off of all the intellectual faculties. This sort of gingerbread is baked daily and more sedulously than pure wheat or rye-and-Indian in almost every oven, and finds a surer market.“

Poor entertainment/information leads to poor “intellectual faculties.” When one consumes poisonous material, one will, essentially: “vegetate and dissipate their faculties” (Thoreau: Walden, 1854). Imagine this is an issue Thoreau contemplated and saw the dangers of almost 200 years ago; and presently, with the coming of the second quarter of the 21st century, his prophesy appears to have been made real. I daresay (and God, how I feel old and archaic saying it) that we have a crisis at our hands. We are, it seems, headed for a collective, intellectual degradation.

Prof. Harold Bloom puts it like this,

“Unfortunately, nothing ever will be the same because the art and passion of reading well and deeply, which was the foundation of our enterprise, depended upon people who were fanatical readers when they were still small children. Even devoted and solitary readers are now necessarily beleaguered, because they cannot be certain that fresh generations will rise up to prefer Shakespeare and Dante to all other writers. The shadows lengthen in our evening land, and we approach the second millennium expecting further shadowing.” (Bloom: The Western Canon, 1994)

And put differently by Thoreau, though in the same spirit:

“To read well, that is, to read true books in a true spirit, is a noble exercise, and one that will task the reader more than any exercise which the customs of the day esteem. It requires a training such as the athletes underwent, the steady intention almost of the whole life to this object.”

Reading the classics is not a process of weeks or months, but in Thoreau’s words: “it requires a training such as the athletes underwent,” meaning it is a project of a lifetime. It requires serious dedication to this craft of which the essence is to read and reread the classics, and to wrestle, as if our soul’s depended on it, with our canon. This is for both Thoreau the man, and the character, a crucial step toward the true ‘art of living well.’

One may ask then: Why? What is there to gain by committing to this life-long exercise?

Well, outside The Western Canon’s power to truly change our intellectual, cognitive and spiritual capabilities, literature of the highest aesthetic order has the ability to do something else as well; it can, quite literally: help you. . . While this may come across rather sentimental or romantic, it is something one must consider and consider seriously. Within the Western Canon any given person can find works which can truly resonate with whatever bothers, hurts or troubles one’s soul.

The magnificence is that we can change our lives and our perspectives, we can truly develop with the written word. The classics are not merely words with which passive meanings have been painted with strokes of lesser or larger audacity, but rather “the noblest recorded thoughts of man” (Thoreau, Walden: 1854); and the significant writers, those of whom we can truly deem the greatest: “are a natural and irresistible aristocracy in every society, and, more than kings or emperors, exert an influence on mankind.” (Thoreau, Walden: 1854)

Thoreau further writes,

“It is not all books that are as dull as their readers. There are probably words addressed to our condition exactly, which, if we could really hear and understand, would be more salutary than the morning or the spring to our lives, and possibly put a new aspect on the face of things for us. How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book.”

Thoreau is right when asserting “to our condition exactly“; which seems to me a statement of such staggering importance as today, the vast majority of people are riddled with just that: conditions.

As for the second aspect I feel compelled to illuminate, solitude, I find it important to note that Thoreau was an avid reader of my own literary hero in Michel De Montaigne. For Thoreau, the concept of living with deliberation, self-reflection, and achieving this through some praxis of both solitude and deep reading is more or less directly derived from Montaigne.

While this is not an essay on Montaigne, and while this essay (as is typical for me) is starting to grow uncomfortably in length; as I am writing this, in the shifting light of an oil lamp I have hung from the ceiling in a chain, which currently, as if on a ship to sea, is rocking with the motion of the wind, presently hammering onto the rooftop; so that the words in my notebook appear to move on their own accord, in a light almost red as it is filtering through a cerise glass, giving to the room a rather spooky implication, I have been forced to remove many pages now, as an essay such as this, on an exemplary work like Walden, can go on and on, and I do not yet, it seems, possess the quality of limitation one finds with the best of essayists in Montaigne or Emerson. — But, one can hope this will come (at least to an extent), with experience, with will, with practice. . .

In any case, Montaigne’s own essay on solitude is no doubt ingrained deeply within Thoreau’s own thoughts on the subject matter. While Thoreau retreated to the woods, “Montaigne himself had withdrawn in solitude to his estates, as many an ancient philosopher and statesmen had done, with leisure to seek after wisdom, goodness and tranquility of mind.” (M.A. Screech: 2003).

It seems obvious that Thoreau, who was reading Montaigne deeply, was no doubt inspired by this process. As one reads the two side by side one will see many similarities between that of Montaigne and Thoreau,

“Ambition, covetousness, irresolution, fear and desires do not abandon us just because we have changed our landscape.“

So writes Montaigne, which interestingly parallels well with Thoreau who was of the opinion that it should not matter where the soil one is to reach into is located (geographically), whether near or far away; it is about being present and deliberate, when one is to settle in one’s solitude.

Thoreau, like Montaigne, is of the notion that solitude can come about in many ways, and that moving to the woods, as Thoreau did, or moving to one’s isolated estate, as Montaigne did, is not necessarily the ‘correct way’, as solitude can essentially come about anywhere.

Montaigne writes,

“You do more harm than good to a patient by moving him about: you shake his illness down into the sack, just as you drive stakes in by pulling and waggling them about. That is why it is not enough to withdraw from the mob, not enough to go to another place: we have to withdraw from such attributes of the mob as are within us. It is our own self we have to isolate and take back into possession.”

Call it Walden Pond or Château de Montaigne, little does it matter if one cannot isolate one’s self and “take it back into possession.” Like Whitman writes in Song Of Myself:

“The delight alone or in the rush of the streets, or along

the fields and hill-sides.”

Solitude: or living with deliberation and isolating one’s self can certainly take place in solitary confinement in the woods, but it is equally to be found “in the rush of the streets” where the learned, or the poet, or the philosopher (whichever way one wants to describe it) has already isolated one’s self and extracted the mob from “within us.”

Thoreau is in obvious agreement as he writes,

“Solitude is not measured by the miles of space that intervene between a man and his fellows.”

And in the same chapter, he gives a wonderful (and somewhat tragicomic) analogy to the farmer,

“The farmer can work alone in the field or the woods all day, hoeing or chopping, and not feel lonesome, because he is employed; but when he comes home at night he cannot sit down in a room alone, at the mercy of his thoughts, but must be where he can ‘see the folks’, and recreate, and as he thinks remunerate, himself for his day’s solitude; and hence he wonders how the student can sit alone in the house all night and most of the day without ennui and ‘the blues;’ but he does not realise that the student, though in the house, is still at work in his field, and chopping in his woods, as the farmer in his, and in turn seeks the same recreation and society that the latter does, though it may be a more condensed form of it.”

I find this analogy important. We all have to work, it is in most cases as unavoidable as the sun rising in east, however, what one does when one comes home is what makes or breaks our soul. Does one, as most does, fall prey to the cheap screens and poor social media platforms which will no doubt accelerate a slow rot of our selfhood, or, does one actually cultivate one’s self. Having “the blues” as Thoreau notes, should not be a possibility for the serious reader, or, for the artist, or for anyone else seeking to delve deep into what both Montaigne and Thoreau so ominously dubs the ‘awakening.’

An awakening not to be confused with the modern, rather hip lingo with which the word is being casually thrown around and is being connected with an often absurd plethora of conspiracies and recreational drugs; no, there is talk of something radically different — and much the deeper. Something which takes time; and of which the great Horace has encapsulated so well in his Epistles:

“In culpa est animus qui se non effugit unquam” translated to: “That mind is at fault which never escapes from itself.”

It is this escape exactly both Thoreau and Montaigne so stubbornly paves the way for, and which is, an absolute necessity for the project of ‘the art of living well.’

As for a few final words on solitude, I find it necessary to point out, that a process of actual aloneness or complete isolation, is, for most of us, likely a necessity. For all the solitude one can require in the rush of the streets or “in towns and in kings’ courts” (Montaigne: Solitude, 1572) it is still, as Montaigne points out: “more conveniently” enjoyed “apart.”

It is important to remember that Thoreau, despite his claims of finding solitude with his peers (Thoreau certainly saw his fellow townsmen often and routinely), did move to the woods, and Montaigne did isolate himself on his estates, and Whitman preached a process which began with some form of isolation, as he notes,

“Houses and rooms, are full of perfumes, the shelves are

crowded with perfumes,

I breathe the fragrance myself and know it and like it,

The distillation would intoxicate me also, but I shall not

let it.“

The perfumes being the modern day tools and ways in which the modern human distracts him/herself. Whitman continues, fabulously,

“The atmosphere is not a perfume, it has no taste of

distillation, it is odorless,

It is for my mouth forever, I am in love with it,

I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised

and naked,

I am mad for it to be in contact with me.“

One is, in a sense, better off (to start with) by removing one’s self entirely, and to get into contact with what Thoreau’s capitalised Nature has to offer, or Montaigne’s long strolls in the quietude of the garden.

To round up this essay, I will lead the reader back to a final Thoreauean point which may be the most accessible and practical, and equally what one can implement in the very moment of finishing this essay.

Simplify, simplify, simplify, my friends.

To Thoreau’s point,

“Our life is frittered away by detail. An honest man has hardly need to count more than his ten fingers, or in extreme cases he may add his ten toes, and lump the rest. Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity!”

and later,

“Simplify, simplify. Instead of three meals a day, if it be necessary eat but one; instead of a hundred dishes, five; and reduce other things in proportion.”

Thoreau was rich as he had less, he was singularly intentional, and above all, he was fanatically deliberate. I will finish this essay with a passage by Thoreau which should, at this point, whether you agree or disagree, at least — unless you are as cold as the machinery on which you read this essay! — stir something within you:

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, livings is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.”

Leave a comment