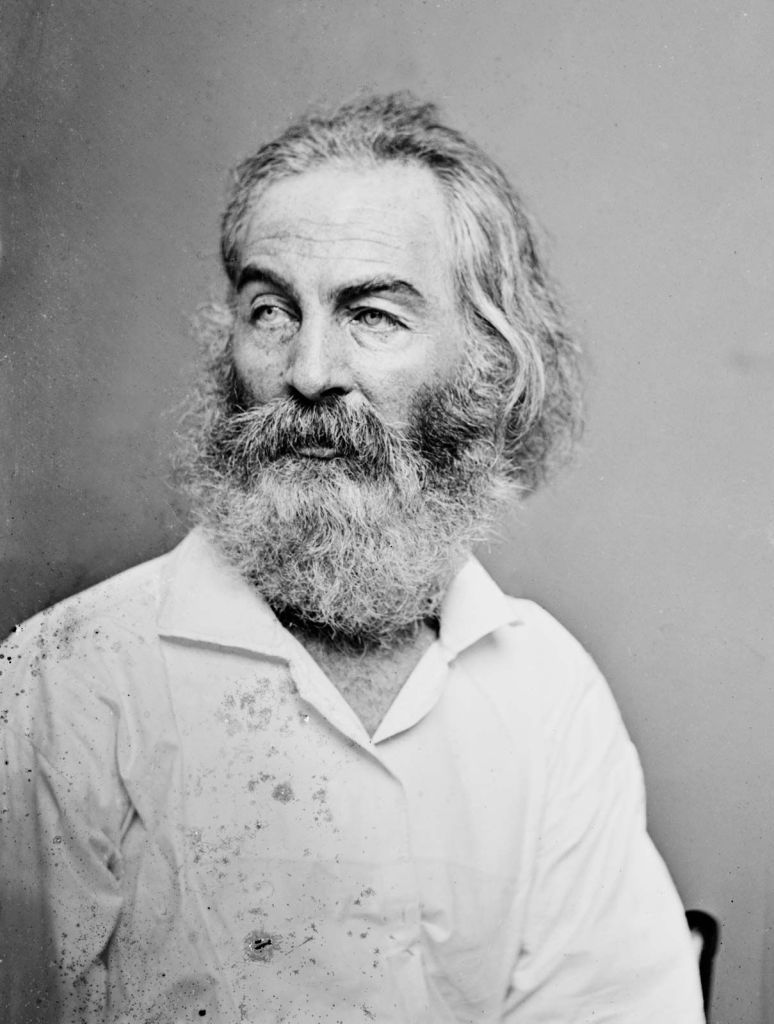

Why Whitman’s Song of Myself?

There is no poem like Song of Myself. Nowhere in literary history does one find such extraordinary originality, reinvention of language, and baffling aesthetic merit as in Song of Myself. Yet, Whitman is still to this day both misunderstood and critically undervalued.

This issue is part one of three issues that will dissect why Song of Myself is one of the most important poems written, and how it weaves the very fabric of human cognition into words. Whitman is not merely the “American poet” as he is often accredited, although he certainly is the greatest poet to come out of the American tradition. Rather, he is the poet of human nature, of the soul, as this issue will attempt to show.

Whitman is rightfully positioned at the centre of Harold Bloom’s The Western Canon, along with Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, Chaucer, Montaigne and twenty other crucial authors who have shaped the Western consciousness. I have in my life read only a handful of works that have been able to tackle the very roots of human cognition, and Whitman’s Song of Myself is one of them. Among other works include Aristotle’s complete works, Hegel’s The Phenomenology of Spirit and The Science of Logic, Shakespeare’s King Lear, Hamlet, Othello, Henry IV and Anthony And Cleopatra, Faulkner’s entire body of work in synchronicity, Montaigne’s Essays, The King James Bible, and to an extend, although I have in later years somewhat parted ways with him: Heidegger’s Being And Time.

(Other worthy candidates: Homer, Plato, Darwin, Chaucer and Dante, however these thinkers can to an extend be sublimated in the aforementioned thinker’s works).

It is obviously a controversial list. However, I stand my ground that these thinkers have tackled human cognition better than any other thinkers within the Western sphere of thought. Aristotle encompasses all of ancient thought. Hegel is sublimating all philosophy from Aristotle to Kant (including Kant) as well as after him up until Heidegger. There is nothing we find in psychology nor in sociology we cannot find in Shakespeare (I am a firm believer in the somewhat contentious Bloomian axiom that there is only a Shakespearean reading of Freud, and not a Freudian reading of Shakespeare). Faulkner shows us human cognition painted onto an extraordinary canvas, synthesizing it with unmatched prose-poetry. Montaigne’s Essays have proven themselves to be the catalyst for all human sciences. And of course, The King James Bible needs no introduction nor justification as it pertains to its immense influence within Western thought.

Song of Myself rank among these groundbreaking works. In this issue I will emphasize, and delve into particular passages from the poem in an attempt to show how Whitman’s work is a project that should be examined and re-examined by the individual reader as well as the institutions for ‘higher learning.’ This issue will not delve into the literary architecture of Whitman’s text, as there are hundreds of thousands of pages of literary criticism on Walt Whitman. Much of which is excellent and does not need further repetition. Rather, this issue will focus on the text’s deep revelations of human cognition, human nature, and the very roots of our ‘Self’. Hence, this issue should be treated as an interpretive assessment rather than literary criticism.

If one wants to learn the facets of Whitman’s language, ex.: metaphors such as ‘perfume’ for human temptations, or his concept of ‘tallies’, or the many autoerotic allegories, one must seek council elsewhere.

If the interest is in a comprehensive, purely literary dive into Whitman’s works I recommend Bloom’s Classic Critical Views in which Harold Bloom thoroughly dissects Whitman’s poetry in Leaves of Grass. Steiner, Kermode, even Price, Folsom and Traubel are also great resources.

Finally, this issue is making use of the Penguin Classics, ‘Walt Whitman: The Complete Poems’ (2004). Any edition of Song of Myself will suffice for the curious reader who is co-studying the poem with this text, so long as it is the 3rd, 1892 edition.

Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself (1892):

Being around 1300 lines in length one must in a format such as this choose rather selectively. Certainly every line contains within it extraordinary truth(s), but one must filter. A task that is both difficult and possibly problematic. I have chosen passages that resonates with several layers of cognitive complexity, and while many passages have been left out it is not for a lack of appreciation nor understanding, however, there is only so much time and space. The aim is not a line-for-line analysis, rather this three-part series on Song of Myself should catapult the reader into reading and comprehending the text themselves.

As a final recommendation any serious critic with a poetic license to kill will advise: read the text aloud and reread every sentence. Whitman’s poetry especially. This will greatly enhance not just the understanding of the content, but also demystify many facets of the poetic texture. Facets otherwise hidden or resisting immediate interpretation.

1-3:

“I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.”

These are the first three lines of Song of Myself. Much have been made of them, but less will be made of them in this issue, other than to state the obvious. This is a song of Myself, of us, of you and me. And everything good we have, all that belongs to us “belongs to you.” This you has a double-meaning. It is “you” as in us (the reader, each and every one of us), as well as nature itself. Whitman is you, he is me, he is us and the rest, and at the same time, he is none of us.

This is Whitman’s process throughout the entire poem. Whitman is all of us. “I am a free companion” (817) and “I am the hounded slave” (838). He is “the poet of women the same as the man” (426). And more strikingly: “I am not the poet of goodness only, I do not decline to be the poet of wickedness also” (463). Whitman is in essence the slave, the rich, the poor, the master, the God(s), the woman, the man, the child, he is all of us, while still being separate from us.

It is the same idea G.W.F Hegel outlines in The Science of Logic with his difficult notion of ‘fürsichsein‘; which is dumbed down to: something is identical to something else (ex.: love and hate are identical to each other), yet they are two separate entities. While Whitman probably had not read Hegel, this thought process is very important, and runs as a pattern through all major Western thinkers, not the least in this poem.

4-6:

“I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.”

The following two lines are rather simple, yet essential as they are part of the Whitmanian process of reflection and inviting one’s soul into the process of reflection. This will require an initial step of solitude, to “loafe”, and not the least being in a natural environment (we shall delve into the process later). Whitman writes somewhat prophetically in a later passage:

“Backward I see in my own days where I sweated through

fog with linguists and contenders,

I have no mocking or arguments, I witness and wait” (80).

Once again, this is the Whitmanian process of taking a step back (our out) as a means to come closer to the truth he is pursing to show us. Rather than engaging in activities that disrupts the process of reflection and observation, it is important to start at the simplest (and at the same time most complex) of steps: the leaf of grass.

Whitman emphasizes this beautifully: “I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journey-work of the stars” (664). This is a crucial passage that goes hand in hand with (6): “observing a spear of summer grass.” For Whitman, the spear of summer grass contains as much truth as any phenomenon one will find in nature, as much truth as any thought, as any idea. The spear of grass is the entire cosmos, just as anything else is the entire cosmos (you, me, the bees humming in the bushes). He later puts this idea to the test in a stunningly beautiful and profound sentence: “All truths wait in all things” (648).

Read this line aloud repeatedly. “All truths wait in all things.” And ponder its meaning with the idea of Hegel’s fürsichsein in mind. It is rather fascinating what comes out on the other side.

28:

“The delight alone or in the rush of the streets,

or along the fields and hill-sides.”

I highlight these two lines as they encompass much of Whitman’s project. He is not a naturalist who finds meaning only in nature, or within the solitude of the natural world, rather truth wait in all things. There is a soulful delight to be found whether you are in the busy streets of New York City, in the countryside of Chile, or contemplating our past in an old Italian hamlet. Among other people, or alone, one will find truth. But first, one must invite one’s soul. Later we shall see how Whitman suggests we do this.

30-37:

“Have you reckon’d a thousand acres much? have you

reckon’d the earth much?

Have you practis’d so long to learn to read?

Have you felt so proud to get at the meaning of poems?

Stop this day and night with me and you shall possess the

origin of all poems,

You shall possess the good of the earth and sun, (there are

millions of suns left,)

You shall no longer take things at second or third hand,

nor look through the eyes of the dead, nor feed on the

spectres in books,

You shall not look through my eyes either, nor take things

from me,

You shall listen to all sides and filter them from your self.”

This is Walt Whitman’s early prophetic promise to us, the reader. He will take us on a difficult journey in Song of Myself. The reader will be confronted with deep truths, and in the end, one will learn how to differentiate between truths in order to get to the idea of truth itself. One shall learn to “filter them”, meaning with enough re-readings of Song of Myself one will build up an apparatus that goes way beyond critical analysis. You may know how to read, you may know how to dissect poems, but these are but fleeting moments considering what Whitman has in store for the serious reader.

What he promises us is at the very core of human cognition.

38-44:

“I have heard what the talkers were talking, the talk of the

beginning and the end,

But I do not talk of the beginning or the end.

There was never any more inception than there is now,

Nor any more youth or age than there is now,

And will never be any more perfection than there is now,

Nor any more heaven or hell than there is now.”

We are still moving within the early part of Song of Myself. These lines are important for a number of reasons. As seen earlier, Whitman has stated “all truths wait in all things” (648). For Whitman, truth is timeless, hence he does not talk of banal concepts such as “the beginning or the end” rather, truth has always been there. We do not have more or less perfection than we have now, “nor any more heaven or hell” than we have now. Truth has always been, and it always will be. Whitman assumes responsibility not to tell us when truth will come upon us, rather he is showing us that it is already there.

One can with a bit of semantic spin on Heidegger’s concept “always already” (immer schon) derive how truth is always here, however it requires the already (being present) in order to observe it. Remember Whitman does not ask us to open the grandiose lexicons in order to find what he is presenting us, rather it is an invitation of the soul. I feel inclined to once again return to the beginning and implore of the reader to reread these lines:

“I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass” (4-6).

At this point, I have taken one step forward in order to understand the steps previous. Whitman does in fact give us tools as to how we can invite our souls into this difficult process he is about to reveal in the following 1250 lines of Song of Myself. Let us consider the following passages:

“Houses and rooms are full of perfumes, the shelves are

crowded with perfumes,

I breathe the fragrance myself and know it and like it,

The distillation would intoxicate me also, but I shall not

let it.” (14-16).

The perfumes mentioned are the many temptations and distractions that are constantly veiling themselves between us, our souls, and truth. One must resist them. Hence:

“The atmosphere is not a perfume, it has not taste of

distillation, it is odourless,

It is for my mouth forever, I am in love with it,

I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised

and naked,

I am made for it to be in contact with me.

The smoke of my own breath,

Echos, ripples, buzz’d whispers, love-root, silk-thread,

crotch and vine,

My respiration and inspiration, the beating of my heart,

the passing of blood and air through my lungs,

The sniff of green leaves and dry leaves, and of the shore

and dark-color’d sea-rocks, and of hay in the barn,

The sound of belch’d words of my voice loos’d to the

eddies of the wind (…)” (17-25)

We have already established that truth is to be found “in the rush of the streets or along the fields and hill-sides” (28), however, where distracted and mindless souls are mingling (towns, cities, etc.) one will more easily be distracted. These are places where the perfumes smell the sweetest. The atmosphere however, the fresh air, the cold and indifferent river-water, the bank by the wood, these elements of nature are where one’s self can temporarily do away with distractions, and easily invite one’s soul to the Whitmanian process we are about to witness.

Whitman continues this passage with beautiful imagery of nature, and only at the end does he add: “the rush of the streets”. This is important as he is setting up a sort of ladder of initial importance. First solitude: “the smoke of my own breath” (21) and one’s “respiration and inspiration” (23). Imagine Whitman butt-naked, cool’d from the fresh water, standing in a slant of warm sunlight, breathing in oxygen and truth:

“The smoke of my own breath,

Echos, ripples, buzz’d whispers, love-root, silk-thread,

crotch and vine” (22).

Then he proceeds:

“A few light kisses, a few embraces, a reaching around of arms” (26).

Suddenly Whitman is including the element of the other. Although some have argued this is one’s self that is to be embraced, I beg to differ. This line is as it often is with Whitman’s poetry a double-entrende. We are now moving from solitude to the intimacy of togetherness.

And finally he adds:

“The delight alone or in the rush of the streets” (28) after many lines embracing solitude and nature.

His point is rather simple. Intermingling with the distracted, mindless (possibly confused) souls in the rush of the streets, comes later. First one must simply “loaf” and “observe” that “spear of summer grass.”

In a rather ironic and humours line, Whitman writes in a later passage:

“Knowing the perfect fitness and equanimity of things,

while they discuss I am silent, and go bathe and

admire myself.” (57).

Whitman has already “heard what the talkers were talking” (38) he does not need to intermingle, rather he is on a quest to show us the truth, and reveal to us our soul, which is to be found where? Well, in us, in our self’s. That is to say: in each other as well. It is quite an extraordinary image. “While they discuss I am silent, and go bathe and admire myself.”

Once again, the reader must re-read these lines often and aloud. The outcome is remarkable.

52:

“Clear and sweet is my soul, and clear and sweet is all that

is not my soul.”

This will be the last line addressed in this issue one out of three issues. Whitman reiterates again how truth is to be found in all things. It is our soul that is the truth, a clear and sweet thing, nonetheless everything that is not our soul is equally clear, equally sweet.

Truth truly waits in all things.

Leave a comment