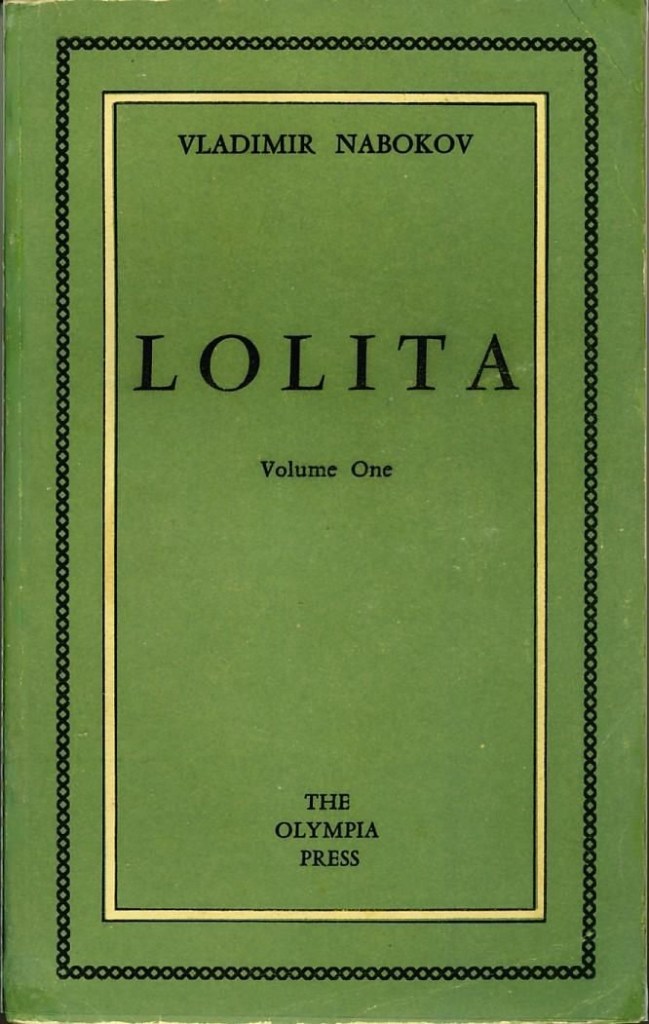

It can be easy in these troubled and confused political times to dismiss Lolita, and effectively Nabokov, just as literary greats such as Neruda, Twain, Tolstoy, Harper Lee, and I have seen even Joseph Conrad among many others, being rather ridiculously subjected to what philosopher Richard Rorty calls a, “subversive, oppositional discourse…” echoing rather apocalyptically Harold Bloom’s essence in The Western Canon and George Steiner’s academic message in After Babel.

While Foucault and Derrida (to an extent Lacan) certainly have brought with them useful branches of thoughts, their quote: “critical theories,” (which turns out to be less critical and more of an exercise in bastardizing the core aesthetic values), historicism and new historicist criticism, and the Marxist theories of criticism, have all turned out, in the end, to undermine the essence of literary study, and, thrust a dagger in the bowels of a tradition under false, and somewhat poorly constructed pretenses.

It hurts that one of the Great Post-War novels in Lolita has to be somehow excused, somehow salvaged from the viciousness of ideology and political activism. It hurts that possibly the greatest poem written in Latin American history and certainly in the 20th century in Canton General is being “canceled”. Yes, ‘the man’ Pablo Neruda was a deeply troubled and flawed character. Admitting in his memoir to have raped a woman. However, this does not exclude his poetry, nor should one neglect the best poem to have been written since Song Of Myself on account of the author’s background.

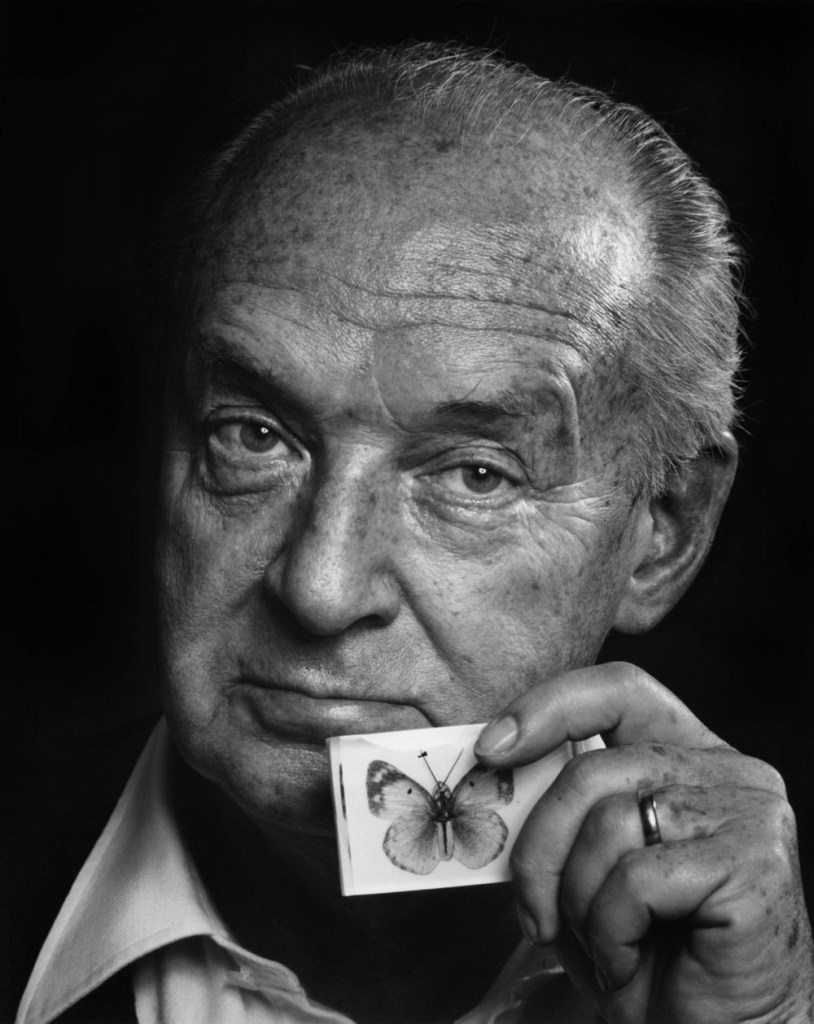

Lolita is, of course, chocking and haunting. While there is a valid criticism in so far as the literary is concerned; that Nabokov probably tried to imitate Proust too much and could not quite succeed. Yet, the prose is as good, and as beautifully construed, as much of what we find in Post-War literature.

And: comparing him to Marcel Proust is a grim approach, who can write like Proust anyway?

But reading about Humbert’s dazzling journey of marrying the mother of Dolores Haze (“Lolita”); and later when she (the mother) dies, Humbert essentially kidnaps the girl, is a grim tale too. And what is more grim? Well, as a reader you cannot somewhat help sympathize with a man who is essentially violating a 12 year old girl. Or, if not to sympathize, then feel some emotional bond to this highly manipulative pedophile; terrorizing the poor girl into thinking she will be institutionalized if their secret is ever revealed.

It is a 101 course in narcissism. And Nabokov has done an excellent job in showing the cognitive representation of both sides: the victim and the perpetrator. Written in the language of a true prose-poet.

Because Nabokov is just that: a prose-poet at heart, who can rival that of Joyce and Woolf. The pleasure of reading his prose is almost an addictive one, and no doubt one’s sympathy for Humbert is as much the psychological portrait as it is one of poetic allurement.

Leave a comment